I am a linguaphile. Studying languages is not only my passion. It has been my companion during difficult times: I learned French in college while feeling anxious about my career choice; German during my first marriage meltdown; Arabic after a midlife crisis; and, recently, Quechua during months of lockdown and solitude.

I spend hours learning the language’s inventory of sounds and how to place my tongue and lips. I dive into the grammar as a child would into a ball pool; nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs and verbs are the colored spheres. I love it.

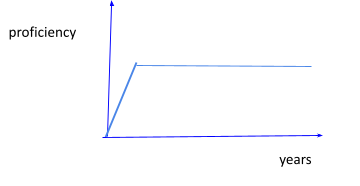

In all honesty, it can be frustrating, time-consuming hard work. My language learning resembles the path of a climber who, after quickly ascending a rock wall, finds herself traversing an arid plain the size of the Tibetan Plateau. Here’s my learning curve.

Learning curve

During the first six months, I learn the language’s basic structure, getting ready to hit the road. Then the cruel reality strikes. As I open my mouth, those perfect sentences shaped in my mind are nowhere to be found. My judging-self looks down on me for failing to speak. The long, tedious and demoralizing journey begins and could last for years. Must learning a language always be this painful? Read on for a better way.

Either cradle or bed?

There is a Spanish motto:

Los idiomas se aprenden en la cuna o en la cama / Languages are learned either in the cradle or in bed.

You learn it as a baby from your parents or as an adult from your lover. There is truth to that. But I see a third option: languages are learned whenever you want, doing something you like. There is no age requirement for learning a language (or any topic for that matter). To learn it fast, you need to need to use it. To learn it painlessly, though, you need to use it in something you are interested in. It is the curiosity of mastering a topic or trade that generates mental connections to absorb new vocabulary and syntax. Travel experiences have proved to be my best language teacher.

Learn Arabic through calligraphy

Imagine you love calligraphy. You happen to be in Palestine, visiting Bethlehem where you meet a great artist whose passion is Arabic calligraphy. You book a class with him. While he shows you how to make the basic strokes you learn that “letter” is Horf in Arabic and its plural is Hurūf. First piece of information: many nouns in Arabic have a broken plural, no magic s there.

As the class unfolds, you hear the teacher use the command write! differently when addressing a woman (uktobi!) than when addressing a man (uktob!). Second valuable datum. But then you realize that every time the master speaks about writing, the k-t-b root is present. Baktob (I write), kāteb (writer) maktūb (what is written, epistle or destiny). You tell the master you know the latter: it is the title of a Paul Coelho book. He nods and writes in beautiful Ruqa’a style: al-maktūb maktūb, or Destiny is written. From that you deduce two things: a) in Arabic there is no verb to be in the present tense and b) predestination is part of the Arab worldview.

Learn Russian through history

Now, fancy you are a history graduate. You are visiting Russia, more precisely you are staying in captivating Saint Petersburg. Keen to learn more about the 1917 Russian revolution, you book a walking tour with a local guide. During your stroll you learn that the city was renamed Petrograd during 1914-1924 and then Leningrad until 1991. Your guide explains that during World War I Russia, wanting to erase all connection to Germany, converted Peter-burg (city of Peter in German) to Petro-grad (city of Peter in Russian).

Saint Petersburg city

After Lenin’s death his followers, the Bolsheviks, changed it to Leningrad (city of Lenin). In the same breath you learn Bolsheviks means those of the majority as opposed to Mensheviks which means those of the minority. Both words come from Russian adverbs: bolshe (more) and menshe (less). Interesting, eh?

Learn Quechua through cultural immersion

I use this technique learning Quechua. After Covid restrictions were lifted, I focused on finding interesting experiences for my startup project Curios, a platform of local encounters for curious travelers in Peru. I met locals from the Cusco Region: farmers, weavers, painters, ceramists, cooks, herders—people whose mother tongue is Quechua though many speak Spanish and a few even English. As I learned their trade I gained vocabulary that would have been difficult to acquire at my desk.

My husband and I met Freddy during a hike to Poq Poq waterfall. Many Quechua words are onomatopoeic; Poq Poq simulates the sound of water falling. Do you know how to say sneeze in Quechua? Achhiy! Freddy guided us during the hike and taught me many nature words: tree (sacha) river (mayu), mountain (urqu), earth (pacha), cloud (phuyu), star (chaska, Freddy’s daughter’s name), fish (chawlla).

With another couple we spent a day at a farming community in the hills above Lamay, where we used the ancestral foot plow: chakitaqlla (chaki, foot – taqlla, stick or handle); harvested quinoa (kinua); built a huatia, an earthen oven where we cooked potatoes (papa); prepared uchukuta. There’s nothing more delicious than potatoes with uchukuta, the meal we shared with the community.

Bruce harvesting quinoa

My friends and I sitting with the weavers of Pumaqwasin by the Piuray Lake

With a group of female friends I visited Pumaqwasin, an association of female weavers. They received us with a ritual in Piuray’s lake (qocha) to ask Mother Earth for a good day of labor. They taught us how to produce a lliklla, a blanket used by women in the highlands. We learned the entire process: from shearing the wool (wilma rutuy) to spinning (phuchkay) with the spindle (puchka), to dyeing with natural ingredients: yellow (q’illu) with q’olle flower, purple (kulli) with cochineal insect, brown (ch’umpi) with walnut tree leaves, green (q’umir) with molle tree fruit, gray (ch’iqchi) with eucalyptus wood ashes; to weaving (away) in the loom (awana). Amazing!

Making learning fun!

There is something about learning a word in its natural context. Don’t ask me what. It just sticks!

Interested in learning Spanish (or Quechua) on your visit to Peru? You have so many experiences to choose from: whether you enjoy cooking or just eating; hiking or horseback riding; ceramics, painting or linoleum carving. Even if you know little of the language, don’t worry. Enjoy, relax and let it flow. As you learn that new skill, new words will follow. Your next Curios travel experience may be your best language teacher.